7 Risk analysis and prevention

Jan Johansson and Bo Johansson

A heavy responsibility for safe mines lies on the mine planners’ shoulders. They must find solutions that promote high productivity and good economy and safety and a healthy work environment. The mine planners will initially shape the general and specific work environment for miners for many years to come. If the planners design a poor solution and it is necessary to redesign it, it will also probably be very expensive to correct after it has been implemented.

Work environment and safety issues are unfortunately often left quite unattended in the early stages of mine planning and design when they instead should be systematically highlighted and developed from the very first planning steps. The best and most efficient means of gaining safety is through proactive planning rather than through reactive corrective actions. It is also the best approach to reducing the associated costs for risk elimination and reduction.

The mine planner is, however, not alone; he or she works in a company context where safety climate and culture, safety policy and safety management have a strong influence on how well the planner can succeed in his or her work.

The slogan “safety first” has been heard in the mining business for many decades but is still in many cases no more than a slogan, since safety first is not fully practised, especially if the business has financial problems. It seems, however, that times are changing and that many mining companies are now making great efforts to improve their safety climate and safety culture. Research on safety has shown that a positive safety climate and well-developed safety culture are important requisites for a healthy and safe work environment, especially in heavy industries.

To manage the risks in the business, every mining company also needs a strategic long-term policy regarding how to deal with safety issues and strive for better work conditions. The safety policy should direct and establish systematic ways to manage (plan, steer and control) the safety work, including early planning and design activities.

Because mining is a very risky business, it has to follow and obey many directives, laws and provisions. Most of these rules only stipulate minimum demands; the companies are free to exceed them. This approach is also what mine planners should aim at, i.e., exceeding minimum demands. A first step for a mine planner is therefore to become acquainted with the national and international (i.e., EU regulations) system of rules and basic demands. Many of these demands are provided by the national or EU authorities, a task that must be done thoroughly in each country; there are quite a large number of directives, laws and provisions that regulate and give guidelines for health and safety issues in underground mining.

The basis for all activities in systematic health and safety work should always be an initial, thorough risk assessment of both the present state and a future planned state. It is of course easier to assess present or historical risks than future risks, especially if the future holds large changes in technology and or work organization. Nevertheless, a mine planner needs to assess the risks associated with different mining concepts that are developed and planned.

Mining might develop in a revolutionary way, but it will most likely develop in another way, in an evolutionary way. In other words, much can be learned from history and from the present state. Thorough evaluations of present and historic designs have for example systematically been used by the Swedish mining company LKAB in the design of their newest main level at 1365 m below the surface. This evaluation has been very important, since the time span from the first conceptual designs to the final solutions has stretched over 12 years and many planners.

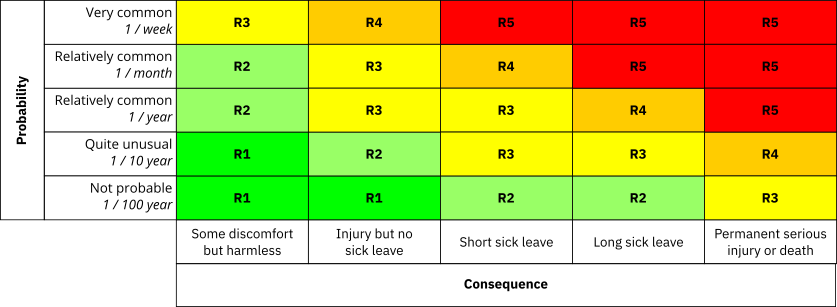

Risk assessments can be performed in number of ways, depending on the situation and circumstances. All risk assessment should however be based on probability and consequences of unwanted events. A practical tool for this purpose is a risk matrix that eases a systematic and consequent risk assessment; see fig. 3

Figure 3: Risk matrix based on probability and consequences.

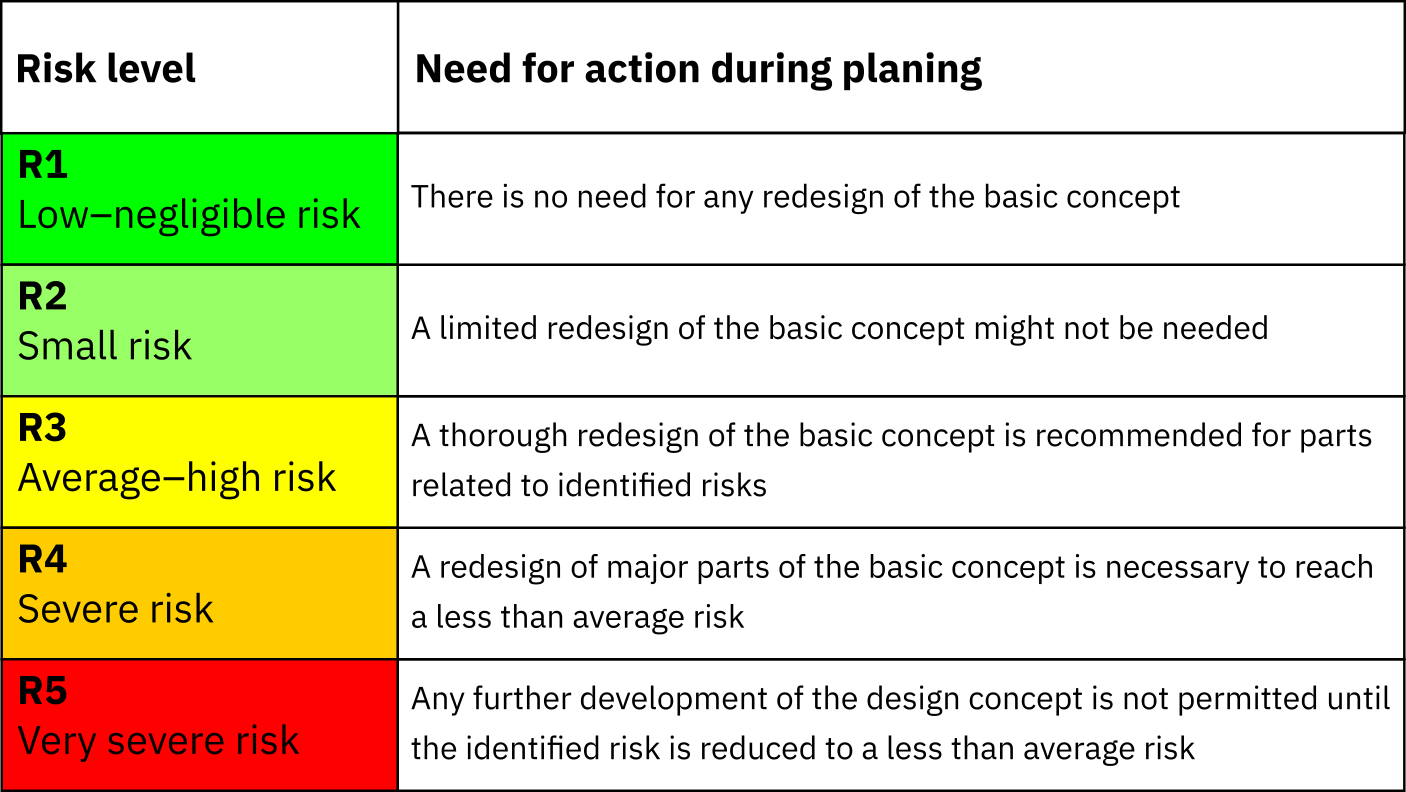

As seen in fig. 3, probability is expressed as a frequency for a specific event or deviation. During planning, the assessed risk level can also be coupled to a specified need for action; see fig. 4

Figure 4: Risk level and need for action during planning.

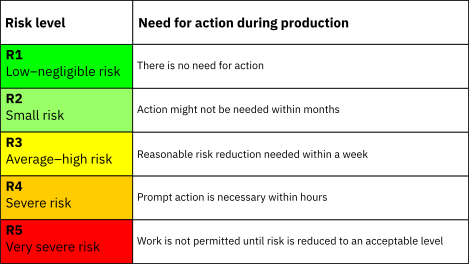

The risk matrix for risk assessments during planning can also, with some modification, be used for risk assessments in the operative production stages (fig. 5). The risk matrix has therefore become a quite well known and used tool in mining companies.

Figure 5: Risk level and need for action during production.

The classical tools for the identification of occupational risks in the existing production environments are safety rounds, incident reporting and accident reporting. These tools are however less suitable to identify and assess risks in future work environments. These environments require other types of more proactive methods such as the following:

Preventive deviation analysis

Preventive energy analysis

According to Harms-Ringdahl (2013), a deviation is defined as an event or condition that deviates from the intended or normal. The purpose of a deviation analysis is to predict and prevent abnormalities that can cause damage and to develop proposals to improve safety measures. Deviation analysis is a very useful method, since it takes into account the entire system, human-technology organization. Energy analysis focusses more on technology and might be useful when developing new productions systems. The three main components considered in an energy analysis are the following:

Energy that can damage

Targets that may be harmed

Barriers to energy

The energies usually considered are the following: gravity, height (including static load), linear motion, rotary motion, stored pressure, electrical energy, heating and cooling, fire and explosion, chemical effects, radiation, and miscellaneous (human movement, sharp edges, and points).

There are also many other different risk analysis methods that can be used in the development of new production systems. In addition to the methods mentioned above, methods such as preventive work safety analysis (PWSA), failure mode effect analysis (FMEA), fault tree analysis (FTA), event tree analysis (ETA), and work environment screening tool (WEST), etc., can be used. The most appropriate tools have to be chosen for every specific analysis task, and the users of the tools must also have the necessary competence to attain reliable and relevant results. Here, the mining business probably can learn much from other industries that have strong safety cultures and long experience of systematic risk management. Especially important will be to learn how to proactively manage risks for fatalities and other severe risks. Here, so-called leading indicators are preferred instead of lagging indicators.

Although there are many risk-evaluation tools available, the mining industry seems to need new and efficient tools for description, evaluation and design of work environments during early phases of strategic decision making and production system design. The most important decisions regarding work environment and safety are made by top management when mining methods, technology, and work organization, etc., are decided. Therefore, risk analyses regarding these matters should be performed as early as possible in the mine design process.

Once a risk analysis is completed, it often requires measures that in most situations should be implemented in the following well-known order:

Prevent in the planning stage; replace the hazards entirely, for example, through automation to eliminate manual or mechanized underground work.

Isolate the individual hazard or risk process, for example, by designing ventilation and layout so that blasting fumes cannot be spread outside the risk zone.

Change process technology and behaviour; for example, employ DTH-drilling with water hydraulics rather than pneumatics to reduce dust emissions.

Limit the hazard through enclosures and physical protection. For example, build concrete borders and railings at the shaft openings.

Isolate personnel from the hazard risk area, for example, by supplying the mining vehicles with safety cabs with good climate control.

Risk is reduced by instructions, procedures, and training, etc., with, for example, procedures for safe handling of explosives.

Risk is reduced through personal protective equipment, for example, functional working clothes.

Depending on the complexity and severity of problems, one may require different combinations of measures as described above. One recommendation is to always try to attack the root causes of the problem first. This approach tends to result in the most cost efficient and result-efficient solutions. This task is important for mine planners. They have the best opportunity to eliminate many potential health and safety problems when they develop the first conceptual solutions. Planners that do not realize this point and neglect these matters can cause great harm for many years to the mining personnel and their company.